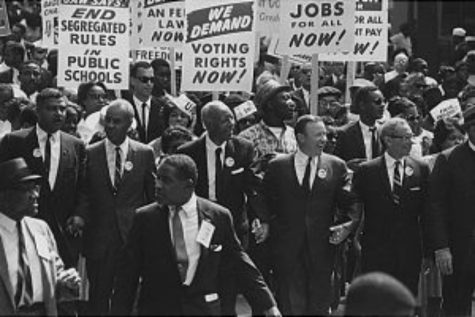

Residents of Flint suffer from polluted water

IMAGE / Nadia Koontz

A protestor holds a water jug promoting clean water at a rally outside of Flint City Hall on Saturday, Jan. 16.

Over 150 people with different backgrounds gathered for one reason only — they want clean water.

The gathering took place outside Flint’s city hall on Saturday, Jan. 16, when Mr. Michael Moore, a documentary filmmaker and political activist, held a press conference to call attention to the plight of Flint residents who get lead-tainted water when they turn on their taps.

Since April 2014, when the water supply from Flint was switched to the Flint River from Detroit, Flint’s water has been polluted by lead that leached from old pipes when the water was not treated properly.

Kale & Gabriela’s Story

Gabriela, a 6-year-old girl from Flint, protests with her father on Saturday, Jan. 16, at Flint’s city hall.

One Flint resident, Kale, who wanted to be identified by his first name only, is a loving and concerned father of 6-year-old Gabriela. Kale is worried that his daughter may be taken away by Child Protective Services because of something he cannot control.

Kale, like many other Flint residents, is fed up with paying for lead-based water. But if he decides to not pay and have his water shut off, Kale is afraid he could receive a visit from CPS, who could take his daughter from him.

Kale has been paying $130 a month for lead-poisoned water while his brother, who lives two blocks out of the city’s limits in Mt. Morris, pays $30 every three months for clean water.

“We’ve been buying bottled water ever since they said they were going to switch over,” Kale said. “Because I am from here, I know how nasty the water is. I don’t want my little girl drinking that nasty water.”

Kale said that he has even witnessed dead animals and other objects floating in the Flint River.

“I have seen dead pit bulls, abandoned cars, and on the news, you’ve seen dead bodies,” Kale said. “No way that is clean water. I don’t want my daughter anywhere near it, but how is she supposed to take baths? You know?”

After pulling her sign down, which read “Stop poisoning us,” and revealing her face, Gabriela shuffled forward to add to her father’s words.

“When we take a bath in the water, our hairs gets all messy and it smells really gross,” Gabriela said.

After comforting his daughter by putting his arm around her, Kale continued.

“No kids should be near that water,” Kale said, while hugging his daughter. “But it is still coming right to their houses and it’s sad because if you’re a parent like myself, you don’t know which is worse, having your kids taken away from you or poisoning them just by having them brushing their teeth.”

In efforts to protect his daughter, Kale said he will continue to drive Gabriela to her mother’s residence in Montrose, which is a 40-minute drive, to have Gabriela bathe and brush her teeth in clean water.

Yazeed Shamieh’s Story

Mr. Yazeed Shamieh is a student at UM-Flint.

Mr. Yazeed Shamieh, a student who majors in microbiology at UM-Flint, attended the clean water rally.

Shamieh is originally from Gaza and graduated from Flushing High School.

He lives in the Flint area, but he said the lead content of his residence is much lower than the content he has found at the university.

“We (other UM-Flint students) were drinking from the water fountains at the university and filling up our water bottles with them,” Shamieh said. “We were filling them up for nine months — nine months — and no one ever told us anything about the water.”

The students of the university just recently noticed the discoloration.

“Then we began investigating every fountain at the university and found that they were all brown,” Shamieh said. “They started putting stickers over the fountains that said the water was filtered, but the water still looks the exact same.”

Shamieh explained that he, and many other students, feel lied to and overlooked.

“I just feel like my safety is not a priority to Flint, and neither do my family or other residents,” Shamieh said.

Cholyonda & Odie Brown’s Story

Holding a picture of her mother, Ms. Cholyonda Brown tells a man the story of her mother’s death due to Legionnaires’ disease at a clean water protest outside of Flint City Hall on Saturday, Jan. 16.

Ms. Cholyonda Brown knows that her mother, Mrs. Odie Brown, 65, was far from safe from drinking the water in Flint.

Odie died from Legionnaires’ disease Jan. 9, 2015.

When Odie arrived at a Flint hospital in December 2014, she was only expected to be there for one or two days to resolve some breathing problems easily.

By Christmas Day, Odie had contracted Legionnaires’ disease. According to the CDC, a bacteria found in water called Legionella can cause illness. When the bacteria infects the lungs, it results in pneumonia.

Legionella pneumonia was Odie’s cause of death. It’s still unclear how she became infected with pneumonia exactly.

“They had several cases besides my mother’s and still kept it from us,” Cholyonda said.

Cholyonda, like her family, is devastated and blames the Flint water, because just a couple months prior to Odie’s death is when the switch to the Flint River began.

“This could have been prevented,” Cholyonda said. “I know they haven’t connected the Legionnaires’ cases to the water yet, but I feel it in my heart that it’s there. My mother didn’t die for nothing.”

There have been 87 cases of Legionnaires’ disease from June 2014 to November 2015 and nine were fatal.

Still, the state refuses to release the names of the nine victims.

“I just don’t want the kids to end up like my mother,” Cholyonda said. “This is sad and we need to do something about it.”

(This story was updated after its publication to decrease the number of deaths due to Legionnaires’ disease from 10 to nine after officials from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services revised the official number of deaths due to the disease on Thursday, Jan. 21.)

Class: Senior

Extracurricular Activities: Student Council, DECA, robotics

Sports: Tennis

Hobbies/Interests: Reading, writing

Plans after High...