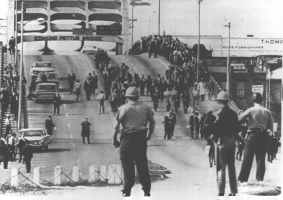

IMAGE / Mr. Peter Pettus / Wikimedia Commons

Protesters marching in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., in 1965.

50 years later, the Selma to Montgomery march is a walk to remember

February 26, 2015

February is Black History Month. It is a time to reflect on historic events that shaped American society into what it is today, especially in regards to the advancement of black Americans.

One of those events was the march from Selma, Ala., to the state capital of Montgomery in March 1965. This year is the 50th Anniversary of that march.

It all started in 1963, when a voter registration campaign was launched in Selma by local black Americans. They formed the Dallas County Voters League.

They were soon joined by members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee .

The goal of the campaign was to register blacks to vote.

Even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which forbade the denial of black suffrage, the DCVL was met with strong resistance when it tried to register blacks to vote in many southern states, including Alabama.

Almost half of Selma’s population was black, but due to fierce discrimination, only 2 percent of that half were registered voters.

The DCVL soon invited the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to join the campaign, along with the Southern Christian Leadership Council.

King’s high profile led the DCVL to believe that his support would draw international attention.

Soon after joining the effort, King and the SCLC decided to make Selma the focus of the voter registration campaign in early 1965.

Law enforcement officers await demonstrators at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in March 1965.

Selma’s governor, Mr. George Wallace, and Dallas County sheriff, Mr. Jim Clark, were strong supporters of segregation.

Wallace and Clark led a steadfast opposition to the registration of black Americans.

The SCLC and King anticipated that the cruelty and brutality against voters by the local law enforcement would attract national attention.

This made Selma a desirable focus point for the campaign.

They hoped the attention would pressure President Lyndon B. Johnson and Congress into enacting new voting rights legislation.

Junior Brandon Wade agrees that the campaign’s location choice was a “smart” one.

“With blacks making up almost half of the population, it was time for Selma to have equality,” Wade said. “Selma was a great start for the campaign and a great place to create change.”

The first march took place on March 7, 1965.

Around 600 people gathered at a downtown church, briefly kneeling and praying. They then began silently walking in rows of two, down U.S. Route 80 toward Montgomery.

The march was headed by Mr. Hosea Williams, member of the SCLC, and Mr. John Lewis, Chairman of the SNCC.

However, it was stopped after only six blocks by Alabama State Troopers, sheriff’s deputies, and other non-supporters near the outskirts of Selma.

Police attack protesters on “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965.

Wielding tear gas, clubs, bullwhips, and more, the officers waded into the crowd, beating the nonviolent protesters on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Unarmed, the protesters were forced to head back to Selma.

Fifty-eight people were treated at the local hospital due to the violent retaliation against the protesters, and the march was later dubbed “Bloody Sunday.”

King urged protesters to join the second march, which was scheduled for March 9.

Media coverage of the march that showed graphic images and video clips outraged many Americans.

Mr. Jack Linn, U.S. History teacher, said the media attention contributed to the success of the second march.

“It caught the nation’s attention, which brought thousands of marchers to the second march,” Linn said.

Within 48 hours of the march, demonstrations in support of the marchers were held in about 80 cities.

President Johnson urged King to hold off the second march until protection for them could be provided. Federal District Court Judge Frank Johnson, Jr. also notified the movement attorney, Mr. Fred Gray, of plans to issue a restraining order, which would delay the march until at least March 11.

Supporters of the Selma marchers in Harlem, N.Y., March 15, 1965.

After seeking counsel and advice from other civil rights leaders and officials from the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, King decided to continue with the scheduled plans.

Over 2,000 people traveled to Selma to participate in the march.

Once the marchers reached the site of Sunday’s confrontation, King asked all of the marchers to stop and pray.

After making their point, they then walked back to Selma. They avoided another attack from officers and the issue of following Judge Johnson’s court order.

President Johnson then promised to introduce a voting rights bill to Congress within a few days.

Later in the evening, several local whites attacked a white Unitarian Minister who had come to Selma to support the protest. He died two days later.

This added to the national concern over Selma.

President Johnson later met with Gov. Wallace, urging him to protect the marchers and start supporting universal suffrage.

On March 16, Selma demonstrators submitted a thorough plan for the next march, which Judge Johnson approved. He banned Wallace and local law enforcement from harassing, threatening, and hurting marchers.

The next day President Johnson submitted voting rights legislation to Congress.

The next march was held March 21 and was federally sanctioned for the safety of the marchers.

By the last day, the number of demonstrators had risen to about 25,000.

The demonstrators covered between 7 to 17 miles per day, and they camped out on the lawns of their supporters.

Once reaching the steps of the state capitol, the marchers felt a sense of relief and accomplishment.

At the capitol, King spoke.

President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“They told us we wouldn’t get here, King said. “And there were those who said that we would get here only over their dead bodies, but all the world today knows that we are here and we are standing before the forces of power in the state of Alabama saying, ‘We ain’t goin’ to let nobody turn us around.'”

On Aug. 6, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in the presence of King and other civil rights leaders. This act prohibited racial discrimination in voting.

“The march changed our society and country for the better,” Wade said. “Due to what happened at Selma, our nation got one step closer to equality for all.”

BLACK HISTORY MONTH SERIES: This is the fourth story in a series written by The Eclipse in honor of Black History Month.