IMAGE / Public Domain

The Little Rock Nine.

The Little Rock Nine marked a milestone in civil rights history

February 23, 2015

Black History Month is a time when memorable people and events are reflected upon.

The Little Rock Nine was a group that marked a milestone in the civil rights movement.

On May 17, 1954, the Brown vs. Board of Education case was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, ruling the segregation of public schooling unconstitutional, thus calling for the desegregation of all schools in the nation.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had been attempting to register black students in previously all-white schools throughout the South, but many schools had rejected the requests.

Three years after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, many schools in the United States were not yet integrated.

However, in 1955, Virgil Blossom, the superintendent of the Little Rock School District in Little Rock, Ark., developed a plan for the gradual integration of the schools, a plan unanimously approved by the Little Rock School Board.

The plan would be implemented in the fall of the 1957 school year.

In 1957, more than 140 black students signed up to attend Little Rock Central High School. The NAACP selected 39 of those students to go to the school, but only nine students showed up- Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls (now LaNier), Minnijean Brown-Trickey, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Pattillo Beals. The nine were the first black students to ever attend the school.

New York City Mayor Robert Wagner greeting the Little Rock Nine. Pictured, front row, left to right: Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Carlotta Walls, Mayor Wagner, Thelma Mothershed, Gloria Ray; back row, left to right: Terrence Roberts, Ernest Green, Melba Pattillo, Jefferson Thomas.

The group members, known as the Little Rock Nine, knew what they were getting themselves into by being the integrators of Little Rock Central but still decided to do whatever it took to make public schools a place for all races to share.

On Sept. 4, 1957, the first day of school for the nine, a white mob stood at the doors of the school, blocking the students from entering.

Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus also showed his stance on the issue, deploying the Arkansas National Guard to aid the segregationists.

It was then that the sight of soldiers barring the students from entry to the school, later called The Little Rock Crisis, made national headlines, polarizing the nation into those in favor of the desegregation of Little Rock Central and those opposed to it.

On Sept. 9, Little Rock School District issued a statement that condemned the governor’s deployment of soldiers to the school.

Also in response to Faubus’ action, a team of NAACP lawyers brought a case to the city’s federal district court to prevent the governor from blocking the students’ entry.

Even President Dwight Eisenhower summoned Faubus for a meeting, warning him not to defy the Supreme Court’s ruling on the desegregation of public schooling.

However, the black students were still barred from entry to the school by the violent mobs and the soldiers, and on Sept. 22, the students still had not been allowed to enter Little Rock Central.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. took notice of the situation in Little Rock, sending a telegram to Eisenhower. King stated that if the federal government did not take a stand against the racial injustice going on, it would “set the process of integration back 50 years.”

King urged Eisenhower to “take a strong forthright stand in the Little Rock situation” (King, Sept. 9, 1957).

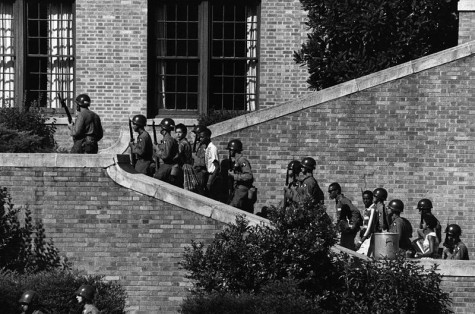

The Little Rock Nine are escorted inside Little Rock Central High School by troops of the 101st Airborne Division of the United States Army.

On Sept. 23, the students actually did enter the school through a side entrance with the help of police escorts. However, they were rushed home soon afterward because of the fear of escalating mob violence.

It was then that Woodrow Wilson Mann, the mayor of Little Rock, also pleaded for Eisenhower to send federal troops to protect the nine students.

On Sept. 24, the president ordered the 101st Airborne Division of the United States Army to federalize the Arkansas National Guard, an action that took the National Guard out of the hands of Faubus.

On Sept. 25, 1957, with the protection of federal troops, the nine students attended their first full day of classes, becoming the first black students to attend a previously all-white high school.

At the end of the school year, Ernest Green, the oldest of the nine, became the first black student to graduate from Little Rock Central High School. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr attended the ceremony.

However, as the school year was drawing to a close, Faubus attempted to postpone the desegregation of Little Rock.

In September 1958, Faubus signed acts that enabled him and the Little Rock School District to close the school district, claiming that the people of Little Rock had to assert their rights and freedom against the federal decision to desegregate the schools.

Faubus won the referendum and the district was closed for the next year.

A lot of people gave the blame for the district’s closure to the black community, making the community a target for hate crimes.

Daisy Bates, the head of the NAACP chapter in Little Rock, was the primary target for the crimes, along with the Little Rock Nine and their families.

The Little Rock Nine pose with Daisy Bates (standing, second from left), Arkansas NAACP leader.

The year the district was closed became known as “The Lost Year.”

In May 1959, however, three of the Little Rock School District’s board members were replaced, and the board began an attempt to reopen the schools.

The district reopened on Aug. 12, 1959, and the black students returned to school.

In 1960, Carlotta Lanier and Jefferson Thomas graduated from the school.

Theresa Mothershed later got a diploma from Little Rock Central after taking correspondence courses and going to summer school in St. Louis.

The nine made civil rights history.

In November 2009, the Little Rock Nine were each awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award given by Congress. This award is given to those who have provided outstanding service to the country.

Eight of the nine are still alive; Jefferson Thomas passed away in 2010.

The surviving of the Little Rock Nine are currently members of the Little Rock Nine Foundation, created to promote the ideals of education for all.

Carlotta Walls LaNier, the youngest of the nine, is the president of the foundation.

Beals, LaNier, Roberts, Brown-Trickey, and Green are also motivational speakers.

“Testament,” the Little Rock Nine Monument, located outside the Arkansas State Capitol.

The things that are not often spoken about, however, are the trials that the Little Rock Nine encountered.

The nine were subjected to both physical and verbal abuse: name-calling, spitting, and shoving.

Beals had acid thrown into her eyes, along with a piece of burning paper thrown on her in a bathroom stall.

Brown-Trickey was harassed by a group of white males during lunchtime. She ended up dropping her lunch on one of the boys, getting suspended for six days, and later getting expelled from the school after more confrontation.

However, their struggles came with results. The Little Rock Nine set an example for schools throughout the United States, showing that integration really can happen.

A few of the nine wrote books documenting their experiences at Little Rock Central High School, like “Lessons from Little Rock” by Terrence Roberts, “Warriors Don’t Cry” by Melba Pattillo Beals, and “A Mighty Long Way” by Carlotta Walls Lanier.

The nine knew that enrolling in Little Rock Central would be difficult, but they still had the courage and strength to do so.

Dr. Terrence Roberts knew what was to come after enrolling at the school, but he still had the courage to continue. Roberts told his story in an exclusive email interview with The Eclipse.

“Every second of every day I wanted to run away from all of the chaos and the physical and mental torment, (but) I knew what we were doing was the right thing to do,” Roberts said. “You will be surprised to find how much you can accomplish when you know without doubt that your mission is righteous.”

Roberts, along with the other eight, knew that what they were doing would bring forth a change in the way schools across the nation were run.

“I knew as well that hundreds of people had died in the fight for justice before I even arrived on the scene. I could not disrespect their efforts by saying no to my opportunity to be involved in the same struggle,” Roberts said.

Since the integration of Little Rock Central High School, there have been many completed feats in the civil rights movement, like the Voters Rights Act of 1965, the Civil Rights Act of 1968, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

However, nation-wide integration is no cause to forget the Little Rock Nine.

Mrs. Carlotta Walls LaNier, who also interviewed with The Eclipse via email, thinks that the legacy behind the Little Rock Nine should still be passed on.

“It is necessary for our young kids to know why they are sitting in a classroom with others that don’t look like them,” LaNier said. “This is all a part of our history and should be studied. Too often, parents or grandparents stop talking about the changes that have taken place over the past 300 years of this country.”

BLACK HISTORY MONTH SERIES: This is the first story in a series written by The Eclipse in honor of Black History Month.

Michael Shaw • Apr 2, 2021 at 9:43 pm

During a lecture given at the Hill School in Pottstown Pennsylvania, Carlotta Walls Lanier recalled a day at Little Rock High. She said she was sitting in a classroom when a Little Rock policeman entered the room. His first words were, “The crowd wants to hang one of these niggers, which one should we take.” The words sent a shiver down my spine. And that is why she said it.