Hunt for the Bismarck 75th Anniversary Series: Bismarck is sunk

The HMS Dorsetshire launched three torpedoes at the Bismarck as the great battleship was sinking.

This is part three in a three-part series.

The Royal Navy closed in on Bismarck on May 27, 1941. The once mighty German battleship was crippled, sailing in circles like a wounded animal.

Bismarck was pinned between Force H coming in from the south and the British Home Fleet racing in from the north. With Bismarck’s port rudder jammed, the warship could not escape.

Any hope of Bismarck getting home to a German port was absolutely out of the question.

Warships HMS King George V and HMS Rodney opened fire on Bismarck. It returned fire, but with the ship unable to steer and listing to port, Bismarck’s gunnery crews were limited in their rate of firing.

The British began to shell the German battleship with no sign of stopping. British gunnery crews on board the ships stuffed cotton in their ears to deaden the sound of the large naval guns firing.

Over 2,800 shells would be fired at Bismarck by Royal Navy warships during the battle.

Adm. Günter Lütjens commanded naval operations aboard the Bismarck.

Bismarck attempted to fight back, but as shells rained down on the battleship, its large gun turrets were knocked out, ravaging the ship and killing numerous German sailors.

At one point, a salvo fired by HMS Rodney devastated the Bismarck’s forward superstructure, severely damaging the forward gun turrets and killing hundreds of sailors. The explosion may have also killed Adm. Günther Lütjens and Capt. Ernst Lindemann along with a number of Bismarck’s senior officers stationed in the bridge.

Bismarck fought on against the British ships, but by 9:50 a.m., Bismarck’s four heavy gun turrets were destroyed. By 10 a.m., all of its weaponry was silenced.

However, the British ships continued to fire. Bismarck’s crew had not lowered the ship’s ensign, indicating she had surrendered. Until Bismarck sank or struck her ensign, the British would not cease fire.

Executive Officer Hans Oels, the highest ranking officer still alive and determined to save as much of his shipmates as possible, analyzed the situation. Bismarck’s stern was beginning to go down, and the ship had a bad list to port.

If nobody took action, most of Bismarck’s crew would be trapped when the ship eventually rolled over.

Oels gave the orders to scuttle and abandon ship. Gerhard Junack, the chief engineering officer, ordered scuttling charges to be set in the engine room. All was lost, and Oels did not want the British to have the benefit of claiming to have sunk the Bismarck.

A lot of Bismarck crewmen, however, did not try to save themselves. Bismarck survivor Bruno Rzonca recounted in 2003 the scuttling of his ship, and his encounter with some of his shipmates as the Bismarck sank.

“So the last order came through: Abandon ship and leave the doors open,” Rzonca said in 2003. “When the skipper gave the order to abandon the ship, we looked for an exit. I was looking around and saw men sitting on a bench and I asked, ‘Don’t you want to save yourselves?’ They said, ‘There is no ship coming. The water is too cold. The waves too high. We are going down with the ship.'”

The Bismarck is on fire and sinking.

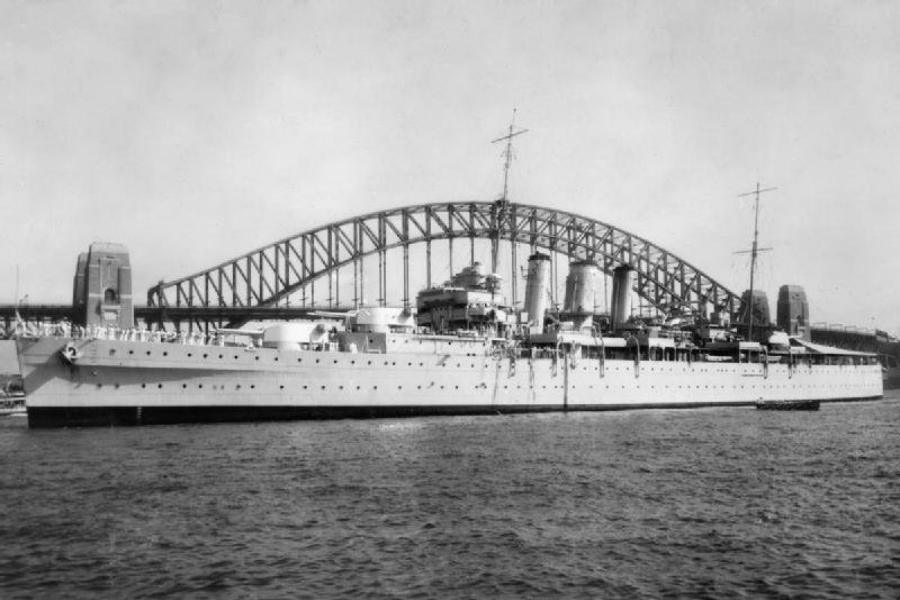

Rzonca made it up on deck and jumped into the water. He was picked up along with other Bismarck survivors by cruiser HMS Dorsetshire.

Unaware of the scuttling order on board Bismarck, HMS Dorsetshire launched three torpedoes at Bismarck to finish the ship off.

However, by the time the torpedoes reached their target, Bismarck began to capsize and the torpedoes hit the upper superstructure of the ship.

Bismarck finally sank at 10:39 a.m., rolling over and sinking beneath the waves. Around 400 Bismarck crewmen survived the sinking and were left swimming in the freezing water.

HMS Maori and Dorsetshire began to pick up survivors, including Rzonca, but left the scene after lookouts on Dorsetshire spotted a possible U-boat.

Since the First World War, the standing order for British ships was to retreat if a U-boat was spotted, even if they were picking up survivors. The British ships were forced to sail away, leaving hundreds of Bismarck crewmen in the frigid water.

Many British sailors on board did not want to leave so many of their German counterparts in the water, where they would freeze to death. The British sailors saw the crewmen of the Bismarck not as their enemies but as fellow counterparts.

The British ships steamed away, picking up around 110 survivors, including Rzonca.

Oels, Lütjens, Lindemann, and over 2,000 other German sailors went down with the Bismarck. The threat of the mighty Bismarck was finally defeated.

The tale of the Bismarck faded into history and was immortalized by the 1960 movie “Sink the Bismarck!”

The HMS Dorsetshire rescued Bismarck survivors from the sea.

In 1989, Bismarck’s wreck was discovered by Dr. Robert Ballard, the oceanographer who had previously discovered the wreck of the RMS Titanic.

Today, 75 years later, few living men can say they participated in the hunt for the Bismarck.

John Coffey, the pilot who crippled the Bismarck is the last surviving pilot to have faced off against the Bismarck. He is now 96.

Ted Briggs, the last surviving sailor of HMS Hood, the only ship to fall victim to Bismarck’s guns, died in 2008, aged 85.

And as of today, out of Bismarck’s 110 survivors, 92-year-old Bernhard Heuer, who survived the sinking as an 18-year-old matrose, a German sailor, is the last sailor of Bismarck’s crew standing and the last survivor of the sinking of the Bismarck.

With the deaths of these men, our last ties to the Hunt for the Bismarck will be forever lost.

Lest we forget the men of Bismarck, Hood, and other sailors who died in the hunt for it.

Senior

Birthday: April 8, 1999

Extracurricular activities: Robotics, quiz bowl

Hobbies: WWI, WWII, and Civil War reenacting; marching band

...