The Edmund Fitzgerald sank 40 years ago

November 10, 2015

Today, Nov. 10, marks 40 years since the sinking of the ill-fated Edmund Fitzgerald in Lake Superior, taking all 29 members of its crew to the bottom.

The Edmund Fitzgerald, launched in 1958, was at one time the largest freighter on the Great Lakes at 729 feet long, 75 feet wide, and 26,417 tons.

The “Mighty Fitz,” as the ship was known, sailed for 17 years until its sinking.

The Fitzgerald hauled iron ore and taconite pellets around the Great Lakes throughout its career, while acting as the flagship of the Olgebay Norton Corporation, taking company officials on excursions around the Great Lakes.

On Nov. 9, 1975, the Edmund Fitzgerald left Superior, Wis., bound for Zug Island near Detroit with a load of taconite pellets.

The remains of one of the Fitzgerald’s lifeboats sits in the S.S. Valley Camp Steamship Museum.

The Fitzgerald was joined by another freighter that same day — the 767-foot lake freighter Arthur M. Anderson captained by Jessie Cooper.

The freighters were met by one of the worst storms in Great Lakes history on Nov. 10, with winds reaching speeds of 50 mph and waves reaching heights of 35 feet in some areas of Lake Superior. The storm rivaled past storms which had famously broke up the lake freighters Carl D. Bradley in 1958 and the Daniel J. Morrell in 1966.

Two survivors were recovered from the Bradley out of a crew of 33 men, while only one man, Dennis Hale, survived the Morrell disaster. Hale died only a few months ago on Sept. 2.

As the waves continued to batter the Fitzgerald and Anderson, the ships made a beeline for safe haven in Whitefish Bay, Mich.

Ernest McSorely, captain of the Fitzgerald, spoke to Cooper as their ships made their way.

One of the ship’s fence railings was also down — a sign that the ship had been bending with the waves. Later on, McSorely reported to Cooper that the Fitzgerald had a heavy list, or tilt to starboard, and that water was coming in faster than they could pump it out.

Around 3:30 p.m., McSorely reported that both of his radars were knocked out. The ship was sailing blind, guided only by the pilothouse of the Anderson.

Around 7:10 p.m., Cooper asked McSorely how the Fitzgerald and its crew were faring.

McSorely said, “We’re holding our own.”

Those words were the last anyone would hear from the Fitzgerald.

Some time after that last conversation, the ship, with its cargo of taconite and 29 crewmen plunged to the bottom and broke in two.

McSorely and his crew perished, with no time to send out a distress signal, only 17 miles away from Whitefish Bay.

To this day, nobody has discovered the reasons as to why the Fitzgerald sank so quickly and without a warning.

Very little of the ship’s furnishings and debris were recovered, with no bodies found. The mangled lifeboats of the ship, offering a mute testimony to the violent demise were found floating around the bay.

In an ironic twist of fate, the U.S. Coast Guard, unable to send out ships of their own, asked Capt. Jessie Cooper to lead the Arthur M. Anderson and its crew back out into the storm after reaching Whitefish Bay. Reluctantly, Cooper turned around and lead the unsuccessful search for survivors of the Fitzgerald, fearful that he would end up like McSorely and the Fitzgerald’s crew.

“You got one on the bottom now,” Cooper said to a Coast Guard official at the time, “and if I go out there you’ll have two on the bottom.”

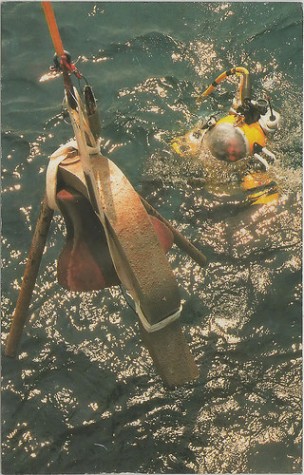

A diver brings up the Fitzgerald’s bell.

The Anderson, unfortunately, found few traces of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

In the spring of 1976, the wreckage was located in two large sections, with the bow of the ship battered and the stern turned upside down, a mute testament to the ship’s violent final moments.

The tale of the ship’s demise and discovery in 1976 led Canadian songwriter and musician Gordon Lightfoot to pen the now famous song, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” bringing the story of the ship to new audiences across the United States and Canada, while sealing its fate as a folktale legend.

In 1995, the Edmund Fitzgerald’s bell was recovered from the wreck after family members of the deceased crew protested to have the wreck site closed off to divers after a body of one of the crewmen was discovered resting outside the ship.

A new bell, inscribed with the names of all 29 of its crew members who went down with the ship was left in place on the ship’s pilot house.

Shortly after the bell’s recovery, the wreck site was closed off permanently to divers by the Canadian government, out of respect for the families, who wished to preserve the Mighty Fitz without scuba divers disturbing the grave site of their loved ones.

The Arthur M. Anderson, now 63 years old, is still in service on the Great Lakes as an ore freighter, just as it was the night the Fitzgerald went down.

The Edmund Fitzgerald’s bell is now on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, in Whitefish Point, 17 miles away from where it was recovered on the bottom.

The Fitzgerald’s life boats are on display at the S.S. Valley Camp Steamship Museum in Ste. Sault Marie, Mich.