Kearsley alumna LeeAnne Walters, Class of ’96, fights for clean water

Mrs. LeeAnne Walters, a Kearsley alumna, holds her 1996 yearbook showing a picture of herself when she was an editor for The Eclipse.

LeeAnne Walters was your average teen who just tried to live a good life after graduating from Kearsley High School in 1996.

She even had big dreams of becoming a journalist.

“My plans changed when I got pregnant in high school with my oldest, Kaylee,” Walters said. “I wanted to be a journalist. I became a medical assistant.”

Little did she know that 20 years later her name would appear hundreds of times in news articles, radio shows, and on news channels across the country. But Walters would not be the journalist writing the story. She would be the source telling her story.

“It was nothing eventful the day of the switch,” Walters said.

What switch?

The Flint water switch.

Walters’ life, as well as her family’s, drastically changed when Flint’s water supply was changed from Detroit’s water to the Flint River in April 2014.

“I developed a rash at the end of May, beginning of June 2014.”

When having it checked out by a dermatologist, Walters said that it was diagnosed as contact dermatitis.

“They’re still calling it that, two years later,” Walters said, shaking her head.

A mother’s search for answers

Walters, a mother to four children who is married to a former sports editor for The Eclipse, did what any other mother would do — she began searching for answers.

Over time, her entire family began to develop rashes. As a family, they had been diagnosed as a carrier of scabies or scabies rash.

“We were told that four times over the course of nine months,” Walters said. “We knew it wasn’t that when one of my twins got it again (in) March of 2015. We knew it wasn’t scabies because it stayed specific to his ankle and his foot for over a month.”

Everyone who came to my house developed a scabies-like rash. That was the first time it wasn’t just us (family) that just got it. So we were all like, ‘OK, what is really going on here?’

— Mrs. LeeAnne Walters

Upset with the answers she was receiving, Walters went to a dermatologist outside of the city in hopes of hearing different results.

“They skin scraped it twice and both times said that it wasn’t scabies,” Walters said.

In August 2014, Walters’ oldest daughter, Kaylee, held her open house right around the time of the boiling advisory.

“Everyone who came to my house developed a scabies-like rash. That was the first time it wasn’t just us (family) that just got it,” Walters said. “So we were all like, ‘OK, what is really going on here?'”

But the mysterious rash was not the only horrifying occurrence that became popular among Walters’ household. In fact, it was only the beginning.

“I went in to go get my hair done in November of 2014,” Walters said, “and my hair lady who had been doing my hair for years was like, ‘What is going on with your hair? Your hair is thinning out.” She’s like, ‘It’s in really bad shape …. I’ve never seen it like this before.’ And I said, ‘I don’t know what’s going on,’ because I really didn’t. Then, I started losing all of my eyelashes. At this point, my kids started losing their hair too, and we all still had the rashes.”

In November around Thanksgiving 2014, Walters’ son, JD, began dealing with dizziness and headaches.

“He was out of school for a month,” Walters said. “He had a sharp, shooting pain in his lower back. He could barely carry his backpack and would double over in pain. The pain would radiate from his left side to the front.”

Walters demanded answers and had tests done.

“First, it was kidney stones,” Walters said. “Then they said his kidneys were enlarged.”

But the diagnoses kept changing. Several misdiagnoses later, the doctors struggled to find an answer.

“At one point, he went in for an emergency CAT scan because they thought that he had cancer. And they couldn’t tell us what was going on.”

A mother’s battle begins

Mrs. LeeAnne Walters and her husband, Mr. Dennis Walters, visited the locker they shared while in high school when they stopped by KHS for an interview in May.

Walters’ and her husband, Mr. Dennis Walters, went to their first Flint City Council meeting in an attempt to find some answers.

Before the meeting, Walters researched clean water information and became knowledgeable about the Environmental Protection Agency‘s guidelines, as well as understanding what total trihalomethanes, known as TTHMs, are.

“When we went in, they (council members) were only giving us half-truths,” Walters said. “I had done research. I knew what they were saying, and I was trying to ask questions. And you could tell that their answers were very scripted. They were repeating the same things over and over again. They had pulled excerpts out of a 1989 EPA guidance on TTHMs, but only pulled out one specific part, and then if you actually googled it and looked it up you would see that the part that they cut off, the bottom, is the fact that hard water, (water that you do not drink), actually increases your risk of TTHMs.”

Walters said she continued to ask questions and was told that her situation did not apply because the council member’s only concerns at the time was drinking water, not hard water.

“So I went home and made it apply,” Walters said. “I pulled up all the house effects I could find. I put them on a sheet, took my references and put those on a sheet, then took them back to City Council, the emergency manager, MDEQ (Michigan Department of Environmental Quality).

“(I) handed them all out at the meeting and said, ‘OK, now it does apply. I’m making it apply. I take water from my tap (and) cook with it for my family. That absorption rate is worse than drinking it cold. Now what are you going to do?'”

Walters took what the council members gave as a response and decided that the answers she received were not enough to justify the dangers her family had been encountering.

She decided to take her questions to the EPA.

From going into these different (Flint) City Council meetings, we were seeing other people there that had discolored water. We were seeing people bringing in files of hair, bags of hair, people who had rashes. So we knew it wasn’t just specific to our home.

— Mrs. LeeAnne Walters

“I called the EPA,” Walters said. “I argued with them about this.”

She said the EPA gave her the runaround. She also said the EPA told her “they’re working on it and that they are going to take it under review.”

Walters then continued to attend meetings and quickly found out that she was not the only one receiving brown water daily.

“From going into these different City Council meetings, we were seeing other people there that had discolored water,” Walters said. “We were seeing people bringing in files of hair, bags of hair, people who had rashes. So we knew it wasn’t just specific to our home.”

After showing up to meeting after meeting and ending up with no results after each one, Walters became fed up.

“We left, we got in the car, and once we got into the car we were like, ‘OK, what do we do?'” Walters said. “How do you fight your city? How do you fight your city and your state? Even if you have physical evidence and still no one is listening to you, what do you do?”

Walters decided that she had to get down to the science of it.

“You can’t argue with science,” she said.

She began collecting data reports, raw water reports, and teaching herself all things about water.

While Walters fought for her family’s health and well-being, her home and water system continued to get worse and her child, Gavin, with an already compromised immune system, suffered.

“We started noticing that he was getting really bad headaches, unexplained fevers, and weight loss,” Walters said. “It got to the point where he could not come into contact with the water at all.”

“He (Gavin) would soak into a tub for five or 10 minutes, get out, and have a water line across his stomach from where he was submerged,” Walters said. “From the waist down, it was basically like peeling his skin off. I would go to put lotion on his skin afterward and he would scream ungodly and cry about how badly it burned. He was terrified and, honestly, I was too.”

Her doctor said to use Benadryl before baths and to only use bottled water. Walters could not get the doctor to test Gavin anymore.

Back at her home, a lead and copper test had been done by the city. The results showed Walters’ water had 104 parts per billion lead in it when the maximum amount should be 15 ppb.

“I immediately called the doctor’s office, was told that I had to wait until they talked to the city, and then was told that I needed a report from the city about the lead content in my water,” Walters said. “So I went and got that report, took it up to the doctor’s office, walked in and said, ‘Look you’ve got two options, either — A — you are going to test my kids or — B — you’re going to write me a letter telling me why exactly you are waiting on the city. And I am not leaving until one of those two things happen.”

Walters sat in the doctor’s office for an hour and a half until the city emailed the doctor for the lab results.

“I went out and got a new pediatrician for my kids after that,” Walters said.

A mother’s child poisoned from her home’s water

This is the flag of the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

On April 2, 2015, Walters and her family found out that Gavin was diagnosed with lead poisoning and had become anemic as a result of it.

After having a nervous breakdown, Walters said she marched to the city of Flint.

“I wanted to ask them what they were going to do to protect our family,” Walters said.

She was then told to fill out a damage claim form.

“I get to the part where you know it says how much do you think this is going to cost, and I have no idea how to fill this out because, honestly, my head is not in this,” Walters said. “I am worried about my kids. They say, ‘Oh, you can put a million dollars on there. We’ll read your claim. Just fill it out.’ And I’m like, ‘No.’ How do you put a price tag on your child or your family?”

Finally, someone from the government assisted her with the battle — Mr. Miguel Del Toral, a regulations manager with the EPA. Walters contacted Del Toral in March 2015.

Walters, suspicious about the water reports, asked Del Toral about corrosion control agents.

“And he says, ‘LeeAnne, what are you talking about?’ And I’m like, ‘These monthly operation reports from the city.’ And he says, ‘OK. Read me off the chemical list.’ So I read it, and he says, ‘No, no, no, no. Read it again.’ So I did, and read it again after that, and he says, ‘No, that can’t be right. Send me a copy of this report.’ So I did. He called me back and said, ‘Oh my God, they aren’t using any corrosion control. They’re breaking a federal law.'”

Del Toral wanted Walters’ home tested. Professor Marc Edwards, a civil and environmental engineer from Virginia Tech University, conducted the test. Edwards is considered one of the nation’s top experts on water treatment and corrosion control.

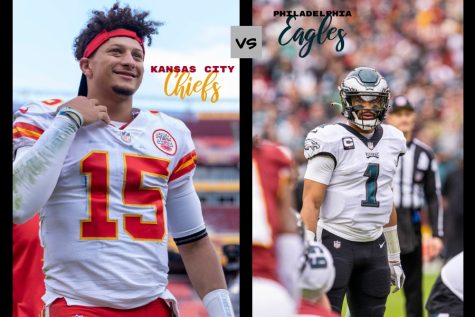

Mrs. LeeAnne Walters’ home tested for 13,500 parts per billion for lead. The EPA recommends concern at only 5 ppb. Water is considered to be toxic at 5,000 ppb.

“We called Virginia Tech and got in contact with Marc Edwards,” Walters said. “We found that my service line is galvanized iron and that the city’s service line is lead. So none of the lead that was coming into my home had anything to do with me (my house’s plumbing).”

The Virignia Tech investigation found Walters’ home to be considered “ground zero” for lead.

Why? Because Walters’ home had 13,500 parts per billion.

What does 13,500 ppb mean? Well, the federal government says 5 ppb is the limit for acceptable drinking water, while 5,000 ppb is considered to be toxic waste.

That means the water in Walters’ home — the water her family drank and bathed in — was more than twice the level of toxic waste.

What was once a comforting and safe home had become a source of poison.

A mother becomes a researcher, fighter

Professor Marc Edwards, a water quality engineer from Virginia Tech University, tested Mrs. LeeAnne Walters home in Flint and found the water to be highly toxic.

After being continuously dismissed by city, state, and federal agencies, Walters felt deflated.

“I called Marc (Edwards) crying and said, ‘Marc, I don’t know what to do. How do we stop this? We have an entire city being poisoned. All of these children are being harmed. What do we do?'”

After a couple minutes, Walters continued.

“I said to him, ‘You know. It’s already too late for my kids. What about all of these other kids?'” Walters said. “How do we stop this?”

Walters and Edwards both decided that they would not quit and would fight the government to prove the water was bad.

They were determined to justify the Flint poisoning of not only Walters’ children, but an entire city of children as well.

From there, Walters joined up with Edwards.

“He (Edwards) said to me, ‘How do you feel about doing some work?’ And I said, ‘OK, what work?’ Then he says, ‘Well, how about we apply for an emergency grant with the national science foundation and we do a citizen sampling in the city of Flint to prove that this is a problem throughout the city?’ (I said), ‘Alright, lets do it.'”

Walters and Edwards both obtained 300 test kits from the grant and made it a statistical test to prove the numbers and avoid having others discredit their results.

“When we got our test results back and proved that there was a problem throughout the entire city,” Walters said, “then we get told that the water is fine and to relax.”

Walters said she became furious soon after that because Flint Mayor Dayne Walling, who was mayor at the time of the water switch, drank the water on TV, assuring people the water was safe.

Walters and Edwards scheduled a press conference to make sure the public learned the information they had about the water — that it was not safe.

While continuing to care for her lead-poisoned son, Gavin, Walters fought with Edwards to get the truth out.

Edwards had been working to get the data on Flint children’s lead levels.

In the meantime, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician from Hurley Medical Center, also wanted to get lead levels from Flint’s children.

Hanna-Attisha gathered the data and went public with the numbers in September 2015.

But when Hanna-Attisha told the public the bad news, Walters said that the state government discredited her.

Less than a month later, Hanna-Attisha’s data was confirmed by other researchers.

“Once the numbers were done again and compared,” Walters said, “it was like, ‘Oh crap, nope. She’s right and we’re (the state) stupid.'”

So on Oct. 1, 2015, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services confirmed that Flint’s children had high lead levels and the Genesee County commissioners declared a public health emergency.

A day later, Walling and other state officials finally announced that Flint’s water was a public health hazard.

The decision was then made to switch back to Detroit’s water system. But the damage had already been done and the pipes had been damaged. It was too late.

A mother fights for clean water in Flint, across the United States

“(In) November 2015, we found out that Flint never had the equipment to run the corrosion controls,” Walters said.

President Barack Obama talks with Gov. Rick Snyder as they arrived at Food Bank of Eastern Michigan in Flint on May 4, 2016. The governor rode in the motorcade with the president from the airport.

Walters said corrosion control would have only costed about $100 a day.

“They (state government) screwed an entire community just to save money,” Walters said, shaking her head.

Frustrated with their city’s leadership, Flint residents voted for a new mayor in the November elections.

Once Mayor Karen Weaver took office, she did not take long to declare a state of emergency in Flint, making the declaration in December 2015.

The next month, Gov. Rick Snyder declared a state of emergency, and less than two weeks later President Barack Obama declared a federal state of emergency over the water crisis.

Sadly, even though city, state, and federal officials recognize that Flint’s water has lead in it, the problem still exists — more than two years after the contamination began and nine months after the city and state publicly acknowledged it.

“But people are still getting lead poisoned,” Walters said. “People are still going without water. We have elderly who still do not have filters. People are scared and rightfully so. We have had issues with Legionnaires’ (disease) on top of it.”

Holding a picture of her mother, Ms. Cholyanda Brown tells a man the story of her mother’s death due to Legionnaire’s disease at a Flint clean water protest outside Flint City Hall on Saturday, Jan. 16.

At this point, 10 people have been pronounced dead from Legionnaires’ disease in the Flint area during the water problems.

The deaths cannot be confirmed that they were a direct result of the water contamination, but officials cannot rule it out either.

So now, Walters is a part of groups working to fix Flint’s water.

Walters said one group she is working with is “making sure the Lead and Copper rule is changed. Not just for Michigan, but the whole entire United States.”

Walters said that this has now become her personal mission.

“I have done a lot of research on that,” Walters said. “There are 19 states that test with similar loopholes such as Michigan. There are only 10 states that I can verify that test in accordance to the law, and there are 21 states that do not make their sheets available so we do not know how they test.”

Today, after the Army transferred her husband, Walters and her family have relocated to Virginia. But for Walters, Virginia is just a part-time home.

“I live in Virginia for the first half of the month,” Walters explained,”going back and forth to (Washington,) D.C., and doing whatever I need to for the citizens, meeting with congressional members. And then I come back and spend the last two weeks of the month working in Flint so that I can keep doing what I am doing because it is very important to me.”

A mother, most importantly, remains a mom

For Mrs. LeeAnne Walters, graduating from Kearsley High School was as exciting to her just as much as any of her classmates.

She took everyday classes, and she worked hard to make it through high school.

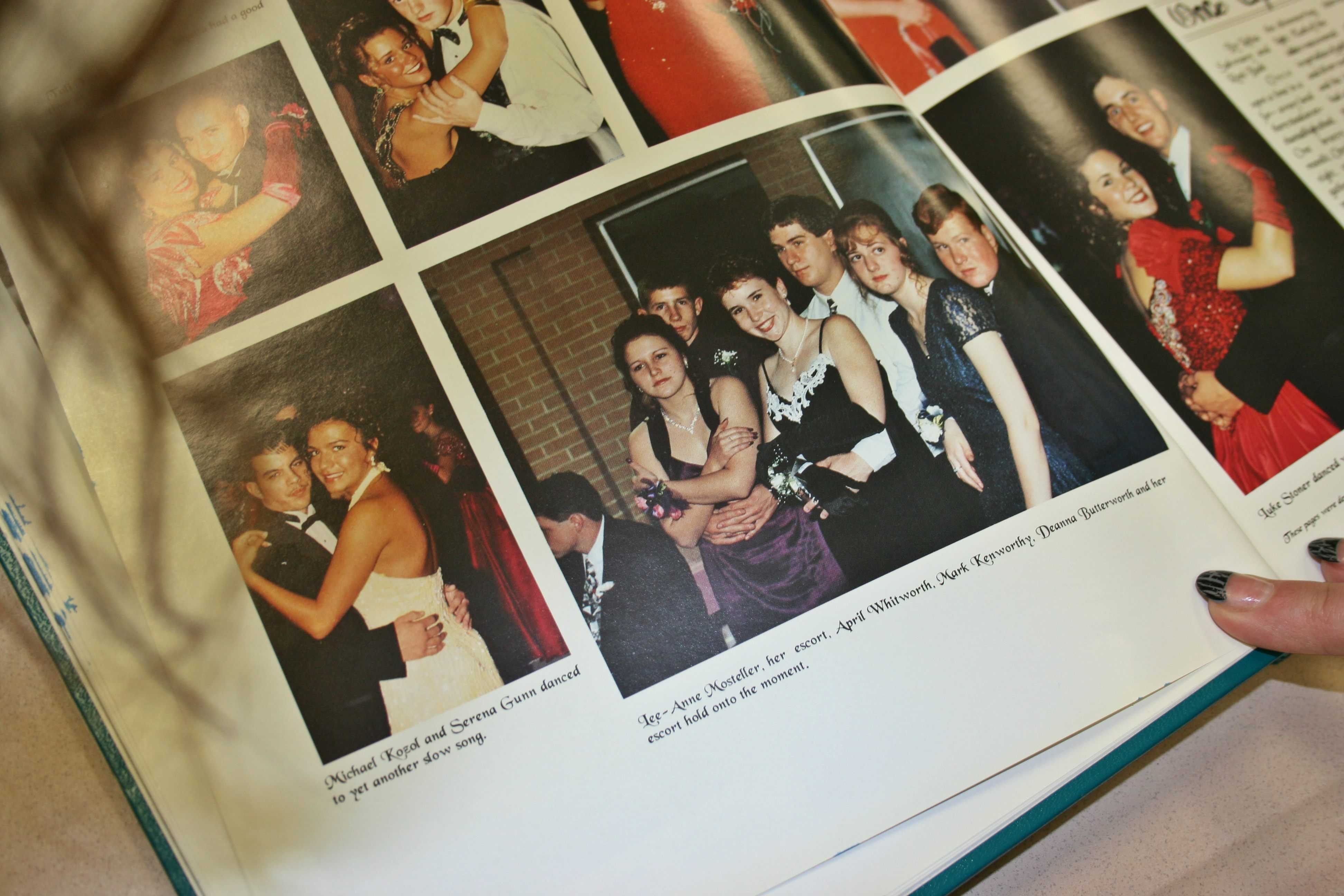

Mrs. LeeAnne Walters, a Kearsley graduate, looks at a prom photo of her friends and her in the 1996 yearbook, Echo.

She was even a part of The Eclipse’s newspaper staff back then, admitting that she often sparred with her journalism adviser, Mr. Darrick Puffer, in her role as an editor. But she said he has always remained her favorite high school teacher.

In addition, with her maiden name — LeeAnne Mosteller — Walters’ name appears many times throughout the 1996 high school yearbook.

Putting Walters’ life in perspective, she simply said that her life after Kearsley has kept her quite busy, especially now that she has been fighting for her family and fellow citizens. Out of all of that, though, she said becoming a mother is the most significant thing she has ever done.

“I have done a lot of things, actually,” Walter said. “But, most importantly, I became a mom. And I liked being a stay-at-home mom more than anything.”

Class: Senior

Extracurricular Activities: Student Council, DECA, robotics

Sports: Tennis

Hobbies/Interests: Reading, writing

Plans after High...